The Shadd farm in Ontario’s Raleigh CSD is an example of a Farm with Established Land Funds, High Non-Dairy Livestock Funds/Flows, and Specialized Animal Products (wool and honey). Abraham Shadd (b. 1801/d. 1882), an affluent free Black man and an abolitionist, was born in Wilmington, Delaware, but also lived in West Chester, Pennsylvania, before moving his family to the Elgin Settlement located in Raleigh Township, in 1852.The Elgin Settlement, also called the Buxton Mission, was a Black settlement that was designed primarily by Reverend William King, a white abolitionist from the United States who had also moved north to colonial Canada.[1] In both Delaware and Pennsylvania, Shadd had participated in the Underground Railroad, assisting Black refugees heading north to freedom. The Fugitive Slave Act passed by the United States Congress in 1850 was behind Shadd’s decision to bring his family further north into Canada West, later called Ontario. The 1850 Act meant that if fugitives were caught, they had to be returned to the slave-owner who claimed them as property and that officials and citizens of the Northern Free States were bound by law to cooperate–although, of course, many did not. Slave chasers were out in force, and the destination for refugees shifted further north across the border. Abraham Shadd had 14 children, several of whom became well known for their own achievements.[2] Shadd himself was the first Black man to be elected to public office in Canada West. Although some earlier references give the date 1859, Carolyn Smardz Frost gives 1862 as the date he was elected alderman for Kent County.[3] In addition to appearing on a commemorative stamp, Shadd was added to the Kent Agricultural Hall of Fame, and Centre Road, which ran through Buxton in 1881 was renamed A. D. Shadd Road in 1994 in his family’s honour.[4]

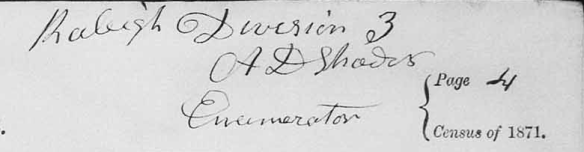

In 1871, Shadd was 70 years old and head of a 103 acre (41.7 ha) farm in Raleigh’s enumeration Division 3.[5] He was listed as a Quaker (“Friends”) and a farmer, and his origin was put down as African. In 1871, the total population of Raleigh CSD’s four divisions was 4,081 with 1,192 (29 percent) listed as African. In schedule 3 of the census, Shadd listed owning 479 acres (193.9 ha) total land in the Dominion of Canada, meaning that 376 acres (152.2 ha) were outside of Division 3. He also listed one town lot.[6] Shadd was also the 1871 Census of Canada enumerator for Division 3. His wife Harriet was 65, and an older woman, Mary, aged 89, lived with them, along with six-year-old Mary A., 14-year-old Andrew, and 23-year-old Eunice. A son, Garrison, who was 32 years old, owned 50 acres (20.2 ha) and a separate house and out-buildings in Division 3. Garrison lived with his wife Harriet, aged 30, and five children, the youngest six months old and the eldest seven. Garrison was listed as a Universalist and a farmer.[7] Garrison worked the land with his father Abraham, so for this energy profile we have combined the land of father and son with the understanding that the farm supported both families.[8] The Buxton National Historic Site & Museum is a treasure trove of historic material about Shadd and his family, and we encourage our readers to investigate their website. One online exhibit (an interactive site) that is particularly exciting to our energy profile is The Shadd Barn, where Abraham Shadd’s original barn, built in 1853, plus his tools may be viewed.[9]

– Figure 1c. Images of the Abraham Shadd barn and homestead. Left: photo of the restored barn at the Buxton Museum. Top right: a virtual exhibit of the Shadd barn, Buxton Museum. Bottom right: an undated watercolour of the Shadd homestead. All photos used with permission of the Buxton Museum.

Figure 1e. Google Map of Raleigh, Kent, Ontario.

Farm Energy Funds

Abraham Shadd’s home farm (the 41.7 ha parcel) was one hundred percent improved, was intensively farmed, and probably supported two families. The first household was Abraham and Harriet and their four dependents, and the second was Abraham’s son Garrison, a farmer who had his own house and 20.2 ha elsewhere in Raleigh’s Division 3. Shadd’s home farm was larger than the average farm in the CSD which was 31.4 ha. Moreover, since the home farm was entirely cleared and the average farm in Raleigh was only 55 percent cleared, Shadd’s potential crop and fodder energy funds (41.7 ha) were much larger than average farm’s (17.2 ha). His hay land, pasture, gardens and orchards were roughly one-third of his land, with the remaining two-thirds in crops. However, his home farm was only about 21 percent of his total land, with most of his land being outside of Division 3. When Garrison’s 20.2 ha is added to Abraham’s total land, then the home farm is about 19.5 percent of their total land combined.

We assume that Abraham and Garrison made good use of their other land by way of sourcing wood and hay and possibly pasturing animals. Although Abraham’s and Garrison’s farms were located in Division 3, their other land was probably located throughout Raleigh’s three other divisions, and Shadd may have bought at least some of it from other settlers who put their land up for sale. In contrast, the Raleigh Census Subdivision (comprising four enumeration divisions) was in a much earlier stage of development than Abraham’s home farm. Just under half of farmland was still in forest, and the remainder was evenly divided between cropland on the one hand, and marshland, pasture, hay land, gardens, and orchards on the other. Abraham kept horses, colts or fillies, milk cows, other horned cattle, sheep, and swine. The Raleigh subdivision (CSD) reported the same livestock types, but Shadd had a greater emphasis on cattle than did the CSD. The livestock intensity of Shadd’s farm was 8.4 livestock units (LU/km2) and the grazing intensity was 1.65 ruminant livestock units per hectare of pasture on the home farm. For the Raleigh CSD, the livestock intensity was higher at 17.0 LU/km2, but the grazing intensity was lower at .82.

Farm Energy Flows

In 1871, the Shadd farm had 25 cords of firewood on hand which may have come from the 152.2 ha of other land that was separate from the home farm. The farm produced 117 bu of fall wheat, 150 bu barley, 17 bu oats, 30 bu peas, one bu beans, 100 bu corn, 20 bu potatoes, 3 bu turnips, 5 bu mangels and other beets, 3 bu carrots, one bu clover seed, 100 pounds grapes, 120 bu apples, and 5 bu of pears and/or plums. The Raleigh CSD reported the same crops as Shadd, plus spring wheat, buckwheat, rye, flax seed, hops, tobacco, and maple sugar. The Shadd farm had a feed deficit of 485,812 MJ and a litter deficit of 270,198 MJ. For the Raleigh CSD, the feed deficit and litter deficit were 236,780 MJ and 70,216 MJ per farm, respectively. Shadd’s feed and litter deficits were over three times greater than the average farm in the CSD.

The Shadd farm’s hay energy was less than its pasture energy, which was the same for the Raleigh CSD.The Shadd farm’s hay energy was 489,880 MJ and its pasture energy was 707,887 MJ. The CSD’s hay energy was 88,537,602 MJ and its pasture energy was 186, 768,382 MJ, which was 286,456 MJ (hay energy) and 135,794 MJ (pasture energy) per farm. The Shadd farm had more energy from hay and pasture than did the average from in the CSD.

In 1871, the Shadd farm had more livestock in all categories than did the average farm in the Raleigh CSD. Abraham and Garrison had two horses over the age of three, four colts or fillies, three milk cows, nine other horned cattle, 27 sheep, and 17 swine. They also had 14 beehives, the largest number of hives on a single farm that we have seen. They slaughtered ten horned cattle, three sheep, and 12 swine. The average farm in the Raleigh CSD had 1.8 horses over the age of three, .8 colts or fillies, 2.4 milk cows, 3.3 other horned cattle, 5.7 sheep, 6.3 swine, and .5 of a beehive. The average farm slaughtered one horned cattle, 4.3 sheep, and five swine. The CSD also had 34 oxen. Abraham and Garrison’s large number of beehives, plus their 100 pounds of reported honey, indicate that they were exploring these animals and their product, honey, for farm income, but probably also for pollination of their crops that required pollination by insects–their peas, apples, grapes, pears and/or plums. Jennifer Bonnell notes that the buffering effect of Great Lake water temperature on surrounding air masses, especially Lake Ontario and Lake Erie, “extended the growing season and supported the development of specialized ‘fruit belts’ that in turn provided excellent sources of pollen and nectar for bees.”[10] Abraham and Garrison Shadd may have been early apiarists benefitting from the unique microclimate created by Lake Erie’s water temperature on the air masses surrounding their farm. Abraham’s grandson William (Garrison’s son, see Figure 1g) “hived a swarm of bees,” 29 June 1884, showing that the apiary carried on after Abraham’s death (see Figure 6b).[11] The Shadd farm had 100 pounds of butter, five pounds of cheese, 110 pounds of wool, but no flannel cloth or linen. The average farm in the CSD, however, had 174 pounds of butter, 2.6 pounds of cheese, 3.4 pounds of honey, 25.7 pound of wool, but 7.3 yards of flannel cloth, and, as for Abraham and Garrison Shadd, no linen.

Conclusion

In 1871, Abraham and Garrison Shadd’s farm was prosperous and compares in land use to other farms we have portrayed in our Farm Energy Profiles series, such as Messier and Houle whose Quebec farms were of the same approximate size and were also 100 percent improved. What differs, however, is the very large amount of other land (152.2 ha) that was situated outside Raleigh’s Division 3. Abraham and Garrison Shadd and the Raleigh CSD produced the largest amounts of corn grain that we have seen so far. Most other parts of Ontario did not reach those levels until the twentieth century. Moreover, Shadd’s farm is the first we have seen with more energy from beef than from milk, and it is also the first we have seen with such a large number of beehives. Innovative apiarists, perhaps Abraham and Garrison Shadd were experimenting with their energy funds and flows to find a new approach that would make the best use of their land and the Elgin settlement’s warm microclimate. Certainly, their large number of beehives suggest that they were boosting pollination for their peas, apples, grapes, pears and/or plums. When Abraham Shadd made the decision to move his family north to the Elgin Settlement in 1852, he relocated to what was perhaps the final destination for many Black refugees fleeing the slavocracy of the United States. At Elgin, Abraham Shadd’s ingenuity flourished in a new locality, and he made his mark not only as the first Black man to be elected to public office in Canada West, but also by his success as a farmer and an apiarist.

[1] Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America (New York, NY: Amistad, 2005), 389-394. Born in Ireland, King immigrated with his family to Ohio, where their farm became a station on the Underground Railroad. Later, he married the daughter of a wealthy slave-owning family based in Louisianna. When his wife died, he found himself her heir and the owner of 14 enslaved people whom he wanted to manumit. He travelled to Toronto where he gained the aid of the Presbyterian Synod, recruited 24 businessmen to oversee finances, and acquired an 18-square-mile (4,662 ha) tract of land near Chatham, Ontario, for a Black settlement. In honour of Lord Elgin, Canada’s Governor General at the time, the group of abolitionists was called the Elgin Association. The standard allotment was a 50-acre parcel. These were sold to Black settlers for $2.50 an acre, either by a lump sum payment or over time. King brought the 14 enslaved people he had inherited from his wife to the Elgin Settlement, and he gave them manumission papers when they crossed the border into Canada West. To learn more about the Underground Railroad in this area see: Chatham-Kent, “Chatham-Kent Underground Railroad,” (n.d) Accessed 23 Febuary, 2022), https://www.chatham-kent.ca/visitck/doandsee/heritage/undergroundrailroad/Pages/default.aspx

[2] Karolyn Smardz Frost, I’ve Got a Home in Glory Land: A Lost Tale of the Underground Railroad (Toronto, ON: Thomas Allen Publishers, 2007), 328. Mary Ann Shadd (Cary), Emaline Shadd, Issac Shadd, and Abraham Shadd were four of Abraham’s children who had many wonderful achievements, including the following: Mary Ann studied law at Howard University and later taught school in Washington, D.C.; Emaline became one of the first female professors at Howard University; Isaac, who had moved back to the Deep South, was elected to the Mississippi House of Representatives; and Abraham became a judge in Arkansas.

[3] Frost, I’ve Got a Home in Glory Land, 295.

[4] “Shadd, Abraham D.,” Kent Agricultural Hall of Fame, (Accessed 23 February 2022) https://www.chatham-kent.ca/aghof/inductees/Pages/Shadd,-Abraham-D.aspx.; “Abraham Doras Shadd,” Farms.com (Accessed 23 February 2022) https://www.farms.com/reflections-on-farm-and-food-history/lives-lived-archive/abraham-doras-shadd

[5] “Abraham Shadd,” 1871 Census of Canada, C-9891, Library and Archives Canada (LAC), Ottawa. Schedule 1, p20 line 5, https://data2.collectionscanada.gc.ca/microform/data2/dm13/d13/006003/c-9891/jpg/4396601_00174.jpg ; Other members of the family were listed as B. Methodists (Black Methodists) and members of the Church of England. Shadd’s grandfather, Hans Schad, was a Hessian mercenary soldier who fought for the British. Hans married a Black woman Elizabeth Jackson, and one of their sons, Jeremiah, and his wife Amelia Cisco, were Abraham’s parents. See “Shadd, Abraham D.,” Kent Agricultural Hall of Fame, (accessed 23 February 2022), https://www.chatham-kent.ca/aghof/inductees/Pages/Shadd,-Abraham-D.aspx.

[6] Shadd may have purchased land from other settlers when they put their land up for sale. A rule of the settlement was that for the first ten years of ownership, should a person decide to sell, he or she could only sell to another Black person. Eventually, white people moved into the area. The settlement school was free to attend, excellent, not segregated, and focussed on academics, including Latin and Greek. It attracted white students, including adults, who took seats in class alongside their Black neighbours. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan, 390, 392; Joyce Shadd Middleton recorded that Shadd owned land in Tilbury East and at least one town lot in Chatham, Ontario. Joyce Shadd Middleton, Bryan Prince, and Karen Evelyn, Something To Hope For. The Story Of The Fugitve Slave Settlement Buxton, Canada West (Buxton: Buxton National Historic Site and Museum, 1999).

[7] “Garrison Shadd,” 1871 Census of Canada, C-9891, LAC. Although Garrison had 50 acres, he did not list any crops, livestock, or wood products in the 1871 census’s schedule 4.

[8] Garrison kept a diary (1881-1889) with the assistance of his sons William, Alfred, Charles, and Issac, and there are many references to farm topics. See “Garrison Shadd Diary Collection,” Rural Diary Archives, (accessed 24 February 2022), https://ruraldiaries.lib.uoguelph.ca/transcribe/collections/show/16

[9] The Buxton National Historic Site & Museum website includes lovely and informative interactive sites, such as The Shadd Barn and the Buxton Schoolhouse. See, (accessed 24 February 2022), http://www.buxtonmuseum.com/

[10] Jennifer L. Bonnell (2020). “Insecticides, Honey Bee Losses and Beekeeper Advocacy in Nineteenth-Century Ontario.” Ontario History, 112(2), 141, https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/onhistory/2020-v112-n2-onhistory05560/1072234ar/

[11] “Shadd Diary & Transcription, 1881-1899: William Shadd, 1881-1885,” Rural Diary Archive, (accessed 24 February 2022), https://ruraldiaries.lib.uoguelph.ca/transcribe/items/show/232. See page 106.