The Maher farm in Ontario’s Windsor County is an example of a Timber Extraction Enterprise with Supporting Livestock and Hay. In the 1871 Census of Canada, Philip Maher (b. 1832/ d. 1907) was reported as a tenant on a 40 acre (16.2 ha) farm. However, schedule 3 of the same census indicates that Philip owned 400 acres (161.8 ha) outside the division within Windsor in which the farm he occupied as a tenant was situated. These 161.8 ha were likely located nearby to where he and his family lived, and he was probably using them for timber extraction. The enumerator put him down as a lumberman, not a farmer nor cultivator. When combined, Philip’s two parcels of land totaled 178 ha. The 16.2 ha that Philip occupied was small compared to the average-sized farm (41.8 ha) of the Windsor census subdivision (CSD) in which it was located. However, when combined with his larger 161.2 ha parcel, the resulting 178 ha unit was 4.25 times the size of the average farm in the Windsor CSD. Philip’s parents, James Maher and Mary Ann Maher (nee Quigley) were both born in Ireland.[1] Philip, however, was born in Quebec, as were his two wives, both Quebecois, and all his children.[2] Sometime before 1853, Philip married Marie Ann Lemaitre dit Duhaime and they had six children, George (b. 1861/ d.unknown) being the eldest son. Philip’s second wife was Mary Julie Millette, and the couple had five children.[3] Philip emigrated to Penobscot, Maine, USA, in 1886, and naturalized in 1892.[4] He was accompanied by Julie, but it is unclear how many of his children made the move with them. His eldest son George was 25 years old at the time, and he had been reported as a clerk five years earlier when the 1881 census had been taken.[5]

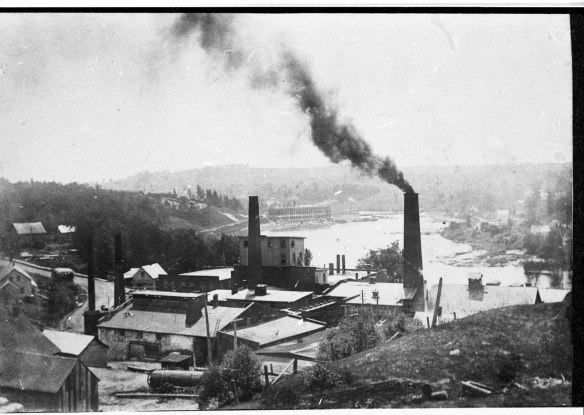

Over the course of 20 years (and three Canada censuses, 1861, 1871, and 1881), Philip’s occupation changed, he became more heavily involved in forestry, and he and his family moved to new localities within the region. In 1861, Philip was a cultivator in Ontario’s Durham County; in 1871, a lumberman in Quebec’s Windsor County; and, in 1881, a timber merchant in Quebec’s Southward County. Philip was a very large firewood producer, reporting 21,500 cords of firewood in the 1871 census when he was located in Windsor. Some of these 21,500 cords were probably extracted from the 161.8 ha of land he reported as owning. However, given the large amount, it is also probable that much of it came from other lands and that he was stockpiling the wood. Philip’s son George may have kept the books for his father Philip’s forestry-based business. Perhaps they were selling cordwood via railway to Montreal customers? Indeed, Philip frequented Montreal’s Albion Hotel, staying there every two to three weeks in the late 1870s and early 1880s, which suggests recurring business trips.[7] A decision in an 1878 Montreal court case showed Philip unscrupulous in an attempt to get land, probably for access to timber.[6] It may also be that the cordwood (no matter how he came by it) was sold to Windsor Mills, a pulp mill in the area that was owned by the Canada Paper Company (Figure 1b). Philip passed at 74 years of age in Maine, USA, and was put down as a lumberman in his death record.[8] His son George, who at some point had also moved to the United States, entered Canada in 1919 and, as reported in the 1921 Census of Canada, was working in Campbellton, New Brunswick, as the manager of a pulp company.[9] Fifty years previous to George’s entry to Canada (in 1871), George’s father Philip had been the “head” of a three-generational family: George was 11 years old at the time, and Philip’s father James who lived with them was 72. James, who was reported to be a farmer in the census, was probably farming the 16.2 ha occupied by his son Philip, and Philip, reported to be a lumberman, was working in forestry. Thus, within three generations, the work of the family had moved from farming, to a mix of farming and forestry, to the management of a forestry-based pulp and paper company. However, our energy profile of this operation illustrates the role of a farm during one year, 1871, of a life spent in wood.

Figure 1d. Google Satellite Image of Windsor CSD and surrounding area.

Farm Energy Funds

In 1871, Philip Maher’s 16.2 ha of occupied land was one hundred percent cleared and virtually all dedicated to hay. However, because we do not know about the 161.8 ha that he owned outside the census division in which the 16.2 ha was located, we cannot ascertain how much of this second parcel was cleared. Nevertheless, we assume Philip was timbering the 161.8 ha and that when it was cleared of forest, he would sell it, perhaps to a settler recently arrived and in want of land.

Philip Maher did not have many animals, at least not on his home farm. He reported having one horse, two swine, three milk cows, and 12 sheep. The draught horses and/or oxen he would have needed in order to extract the cordwood from his 161.8 ha, plus these animals’ feed and litter, must have been reported by another person, perhaps a business partner or the owner of a company Maher was doing the work for, such as a pulp mill. Maher’s livestock intensity was 2.6 animals per km2. The absence of any pasture suggests that Philip’s farm animals loafed in a barn with internal divisions for his horse, swine, milk cows, and sheep. There may have been small paddocks adjacent to a barn for them, as well. The Windsor CSD’s livestock intensity was 4.1 animals per km2 and the grazing intensity was 0.73 ruminants per ha of pasture. Maher’s woodland, we suspect, was the 161.8 ha previously mentioned. The average-sized farm in the Windsor CSD had 26.44 ha of woodland. Maher reported a small garden that was .1 ha in size which is the same size of a garden or orchard for the average-sized farm in the Windsor CSD. Maher did not report any fruit products, so it is plausible that all of this .1 ha was vegetables.

Farm Energy Flows

Philip Maher had three crops, namely potatoes for his family and a small amount of turnips and mangel-wurtzel for his animals, probably his milchers who would benefit from an enriched diet. Conversely, crops grown in the Windsor CSD displayed a much greater variety. Farmers grew turnips (instead of mangels), potatoes, oats, barley, wheat, carrots and other root vegetables, tobacco, peas, apples and other fruits, turnips, beans, rye, buckwheat, and corn.

Maher had no pasture whatsoever, whereas the Windsor CSD had 709 ha of pasture, or approximately 6 ha of pasture per farm, when averaged. Maher had 16 ha in hay, which was 2.8 times greater than the average farm that had 5.7 ha in hay. The Windsor CSD had 677 ha in hay, overall. Maher’s feed deficit was 12,572 MJ, which would have been for the few animals housed on the 16.2 ha he occupied. In contrast, the feed deficit for the Windsor CSD was 15,372,774 MJ, or 129,183 MJ per farm. It may be that by keeping his number of animals low and by putting all his cleared land in hay, rather than combining it with pasture, he had a relatively low feed deficit. The mangels he grew would have supplemented the hay with roots throughout the winter. The remaining feed deficit could have been easily met by bringing in feed from elsewhere. The feed deficit of the average farm in Windsor CSD (129,183 MJ ) was ten times larger than Maher’s.

In 1871, the Philip Maher farm produced more slaughtered meat, except for mutton, and more butter and wool, than the average farm in the Windsor CSD. Maher reported slaughtering two cattle and two swine, and producing 300 pounds of butter and 50 pounds of wool. For the Windsor CSD, the average farmer slaughtered 1.2 cows, 4.1 sheep, and 1.3 swine per farm. The Windsor CSD also had 23,683 pounds of butter and 2,581 pounds of wool, which is 199 pounds of butter and 21.7 pounds of wool per farm. The Windsor CSD additionally produced 1,200 pounds of homemade cheese, 1,502 pounds of honey, 1,935 yards of homemade cloth or flannel, and 16,073 pounds of maple sugar. Maher’s reported 21,500 cords of firewood was 83.67 percent of the total 25,694 cords of firewood reported by the entire Windsor CSD. The average Windsor farm produced approximately 36 cords of firewood, which is more than the average household needed for cooking and warmth. Farmers could sell their surplus firewood to those in the area who needed it–professionals, such as teachers and lawyers, who may not have lived on farms. They may have also shipped their surplus wood via railway to supply Montreal with firewood, sold it to nearby pulp mills, or sold it to timber suppliers such as Philip Maher.

Conclusion

The Windsor CSD had poorer agricultural land than did townships located closer to the St. Lawrence River. This may be why the Windsor CSD was relatively undeveloped at the time the 1871 Census of Canada was taken. Philip Maher may have realized that because of poor soils farming in the area would never provide more than subsistence living. Montreal, an urban centre located approximately 100 km away by rail, was in need of firewood for cooking, heating, and industry and Maher may have set about to meet that need by providing firewood from his 161.8 ha of land. He may also have been supplying wood to local pulp mills. According to testimony given during a court case between the Canada Paper Company and the British American Land Company that took place May 26, 1882 stumpage was worth about $.20 cents per cord.[10] Maher’s 21,500 cords listed on his 1871 census return would have been worth, by 1882 prices, $4,300. Moreover, if one acre (.4 ha) of forest yields approximately 20 cords of wood, then Maher’s 21,500 cords represented 1,025 acres of deforested land. Finally, Maher’s 161.8 ha would have produced 8,000 cords, 13,500 less than he reported. Therefore, Maher must have had tickets to clear other tracts of land but was stockpiling the cordwood on his 161.8 ha parcel. Maher does not report any oxen or draught horses on his 16.2 ha. Thus, he must have outsourced this element of his forestry business. By keeping the number of his farm animals low, doing away with pasture entirely, and putting all his cleared land in hay, he was able to keep his feed deficit low. Being situated near a railway not only made it relatively easy to transport firewood, but it also made it relatively easy to acquire any grains needed to satisfy his animals’ feed deficits. Whereas a family farm provides a place to put down roots and for generations to live on overtime, the business of forest extraction does not necessarily offer the same advantage. As Maher moved from farming into the timber business, first as a lumberman, and later as a timber merchant, he and his family moved to new locations as stands of forest were cut and Maher sought new forests to exploit. Eventually, he moved his family to the State of Maine, just across the border from where he had conducted his Canadian business. Given that he had been in trouble with the law in 1878 over an unscrupulous acquisition of land (see note 6), one wonders if he left Canada, not only to continue and expand in forestry, but to leave the court’s jurisdiction and, thereby, avoid legal altercations.

[1] “Philip Maher,” Maine, U.S., Death Records, 1761-1907, Ancestry.com. The death certificate form asks for the name and nationality of the parents of the deceased person.

[2] “Philip Maher,” 1881 Census of Canada, RG31, C-13199, Library and Archives Canada (LAC). Philip’s first wife Marie Anne Lemaitre dit Duhaime’s birth record confirms that she is Quebecois. See “Marie Anne Lematire Dite Duheme,” Quebec Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1967, s.v. “Marie Anne Lemaitre dit Duhaime,” Ancestry.ca. Philip’s second wife Jane is listed as French in the 1871 Canada Census. See “Philip Maher,” 1871, LAC.

[3] “Philip Maher,” Ancestry Family Trees, Ancestry.ca.

[4] “Philip Maher,” U.S. Naturalization Record Indexes, 1791-1992,” Ancestry.ca.

[5] “Philip Maher,” 1871, LAC. George eventually married a Quebecois woman, Eva (Olivia), but in 1886, when his father Philip left for Penobscot, she would only have been 13 years old. See “George Maher,” Sixth Census of Canada, 1921, RG 31, Folder 34, Census Place 34, Restigouche and Madawaska, page 30, Ancestry.ca. George and Eva (Olivia) had two children, Margaret born in 1902 and George Jr. born in 1908.

[6] “Superior Court — Judgements,” Montreal, April 12, 1878,” Gazette (Montreal, Que.), May 2, 1878. In his search for land to timber, Philip Maher may have been unscrupulous. In the court case Henry Alymer vs Philip Maher, et al, he was found guilty by Judge Johnson of trying to defraud General (Henry) Alymer of Bath, England, of several lots and parts of lots in the Townships of Melbourne, Brompton, and Cleveland. Maher was in cahoots with Henry Alymer Jr. who had “sold” him the land sans any exchange of money without the knowledge of the General. Judge Johnson cancelled the nefarious deed of sale and ascribed costs to the two defendants.

[7] “Hotel Arrivals,” Gazette, (Montreal, Que.), June 12, 1879. Philip Maher frequented The Albion Hotel in the late 1870s and early 1880s. On this particular date both father and son, Philip and George Maher (indicted by the Gazette to be from Sherbrooke), were staying at the hotel.

[8] “Philip Maher,” Maine Death Records, Ancestry.com.

[9] “George Maher, Jr.,” Sixth Census of Canada, 1921, Ancestry.ca. The note that George Maher Jr. entered Canada in 1919 when he was 11 years old only comes up on his particular file. We assume that because of his young age, he arrived in Canada at the same time as the rest of the family. George’s obituary places him in Millinocket, Maine, USA at the time of his death. He was Director of the Public Works Department, and had been working there for 30 years. His wife, who survived him, was Jeannette. His parents were George and Olivia Maher (nee Roy). See “George Maher,” Death and Funerals, Bangor News, (Maine), August 19, 1976.

[10] “Legal Intelligence,” Gazette (Montreal, Que.), May 26, 1882.