The Illustrated Historical Atlas of the Province of Prince Edward Island, colloquially known as Meacham’s Atlas of 1880, was one of the first attempts to map PEI in its entirety. A whole host of information can be found within the atlas; from detailed maps of each of the lots on the island – down to the individual houses, to realistic drawings of prominent citizens and their properties. It is a dream resource for any Island historian!

For us at the GeoREACH lab, the atlas represents yet another opportunity to compile data on energy usage on the island during this period. We can see in the atlas the individual lots that compose our island even to today, each with personalized property information. The cartographers went so far as to outline the individual houses, barns, other infrastructure and property owners for each lot.

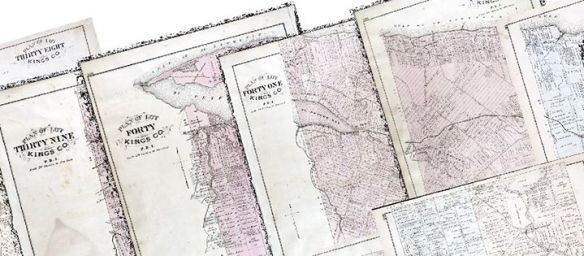

An important step in gathering the data from Meacham’s Atlas was to centralize all the available rasters (individual images) to a single resource. As all the lots were created independently, they would have to be stitched together into a single, geographically accurate map in a process formally known as mosaicing. This is why we have made, using GIS, a comprehensive mosaic of all the lots to easier represent this information.

Beyond that, we also entered data points for the over 16,000 buildings indicated on the map. Though it is still a work in progress, it is now available to be explored. You can adjust the different layers through the content window to look at churches, houses, mills, or schools, or can zoom in to a region you know well to see what it looked like in 1880!