Sails & Tales | Book Reviews

Listening for the Dead Bells: A Review

Megan Lane MacDonald

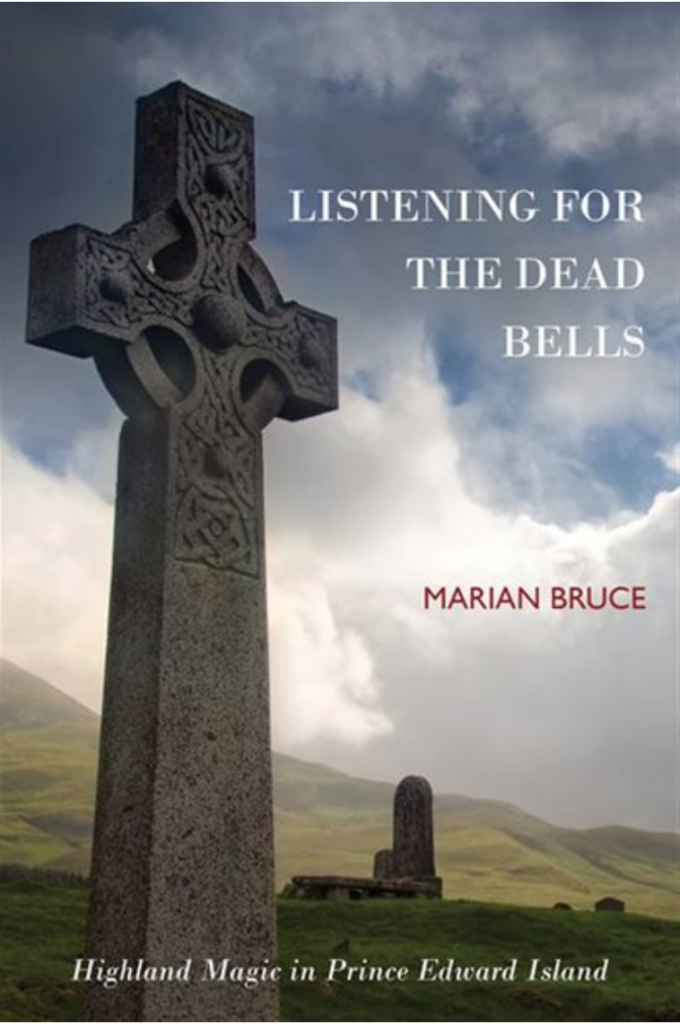

Marian Bruce (2019). Listening for the Dead Bells: Highland Magic in Prince Edward Island. 139pp. Charlottetown, PE: Island Studies Press at UPEI. ISBN: 978-1-988692-29-6. $18.95 CAD

Marian Bruce’s Listening for the Dead Bells: Highland Magic in Prince Edward Island is a collection of supernatural-themed stories sourced from written records and oral histories. These stories are supplied by former residents of Scotland and their descendants who settled in PEI. The accounts that Bruce records feature ghosts, fairies, healing springs, charms, curses, witches, changelings, and, most of all, premonitions. Different kinds of premonitions, such as forerunners, dreams, visions, divination, and visits from the dead, each get their own sections of the book. This book is both educational and entertaining; written for the enjoyment of anyone who loves a spooky tale or has a passion for the art of oral history and island culture. It also provides further interest for readers from PEI who enjoy searching through the stories for the names of familiar communities or families – something that Islanders, in particular, love to do. Bruce highlights the transference of cultural phenomena through immigration and the extraordinary way such cultural knowledge is preserved on islands.

Bruce interlaces stories from PEI with stories from Scotland, frequently crisscrossing back and forth between the Highlands and Island communities to draw comparisons and conclusions. Bruce expertly weaves together a multitude of separate stories, organizing them by theme and tone. Bruce could be accused of being repetitive as she sometimes repeats information from previous chapters when relevant to a new chapter. However, this means that a reader could conceivably pick up the book and choose to read any chapter they wished and still have enough background explanations to follow along.

Bruce never makes value judgements of the stories she shares but will include comments from the storytellers or witnesses contesting the legitimacy of specific events. Bruce is not out to explain away all of the mystery and magic of these stories, yet she still refrains from glossing over contradictions merely for the sake of telling a good story. Her role is that of a records keeper and cultural analyst, recording all the relevant information and addressing how the data was affected by the culture and communities into which it was transplanted. Bruce is mindful of confirming from where and who a story originated, even while discussing multiple stories concurrently. In this way, she properly conveys her sources and relevant information about the storytellers without straying too far into academia. This is in order to accurately convey the transferral of key concepts through time and space from one island to another. For the most part, Bruce manages to do this without overcomplicating the text or creating too much disorder. However, it can be jarring and confusing at times when a short three-line story about a family, meant simply to introduce a topic, leads immediately into a fuller story about an entirely different family altogether.

Bruce dedicates a lot of time to the examination of the intersection between traditional Celtic beliefs and rigid Christian doctrine. She depicts many historical figures who felt that there was no room for pagan superstitions within their theology and their unsuccessful attempts to stamp out such beliefs. However, she points out that many more people of every level of the laity and the cloth saw the two worlds as one and the same. The descriptions that the storytellers give often invoke “the sacred unknown” to defend their beliefs through Christian faith explanations. They explain premonitions as warnings from God to prepare them emotionally for hardships, or to remind them of His grace. Bruce includes these explanations to show how ancestral beliefs were continued on even through the adoption of new religions.

While many Gaelic terms or phrases such as Bòcan, Sluagh, and Dreag appear throughout the book, maintaining the accuracy of the orally transmitted tales, Bruce acknowledges the tragic irony of the fact that all of these stories are recorded in English despite having their roots in traditional Scottish folklore and belief. The final chapter is dedicated to lamenting the death of the Gaelic language in PEI. This is an important element to consider in Bruce’s study. Although much of the cultural phenomena of Scottish folklore and superstition carried over to PEI, the language they were transmitted through died out before the stories themselves did. Bruce argues that both the Gaelic language and the storytelling culture it cultivated have diminished in PEI in recent generations. However, the belief, or the desire for belief, in the supernatural is still present. Younger generations feel disconnected from their ancestors’ stories and views of the world, yet still seek out the unexplained and mysterious. Bruce gives evidence of this through the interest of youth in ghost story events contrasted with the lack of intimate involvement with the subjects of the stories.

Bruce fulfils this desire for the unknown with a treasure trove of interesting and hair-raising stories. She contributes a wealth of information that has not previously been compiled in the same collection until now. Through these stories, Bruce examines the cultural preservation effect that often occurs on islands. When immigrants from the Isle of Skye moved to PEI, they transplanted entire communities and their stories and beliefs came with them. The connections she has drawn between the folklore and supernatural beliefs of Scotland to those of PEI have significant value to the realm of Island Studies.