Changing Island Economies by Dr. James Randall

Chair, Institute of Island Studies

Co-Chair, UNESCO Chair in Island Studies and Sustainability

KEYNOTE ADDRESS

Pingtan (China) International Forum on Island Conservation and Development September 23, 2017

PDF VERSION | ACCOMPANYING POWERPOINT

Introduction

Thanks to the organizing committee for inviting me to this important event and for the hard work they have undertaken to organize this conference. One of the strengths of events such as this is that it allows people from diverse backgrounds, including academia, government and business, to discuss the same issues from very different points of view. Also, I’m an economic geographer by training and have been an island studies professor for the past five years. Therefore, I have a passion for places and an appreciation of the need to take an interdisciplinary approach to address issues.

In my opening remarks I’d like to focus on three main areas:

- First, to discuss the prevailing and competing narratives or stories of islands, how others see islands and how islanders see themselves.

- Second, I’ll speak to some of the characteristics that might lead to the advantages and challenges facing islands in our current global economy.

- Finally, I’ll provide a set of recommendations on economic development on islands, where and why they might flourish and serve as lessons for other islands and coastal regions.

All of this is based on my understanding of the current research on islands and my growing appreciation of what it means to be an islander.

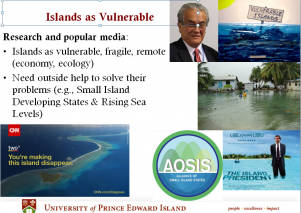

Traditional Narrative

It has been said that islands are the homes to more than 600 million people, or almost one-tenth of the world’s population. Despite this, for much of the past 400 years, we have been conditioned to think of islands as remote, vulnerable and disconnected; defined on the basis of what they don’t have (resources, people, access to markets, economies of scale) rather than what they do have. It has been argued that this perspective has existed since European explorers almost stumbled over islands as they sought wealth, power or a mythical hidden continent. At best, islands were provisioning stations, colonial outposts; remote specks of land in a vast ocean. This has been referred to as an “Islands of the world” perspective. Even today, the language we use reinforces this perspective of islands as tiny specks and as needing outside assistance to solve their problems. For example, it is not uncommon for the tourism industry to appeal to customers by saying that an island is a paradise far from the stresses of everyday life while at the same time the island’s economic development department is lobbying for assistance to decrease transportation costs.

One of the most significant developments of the past generation has been the growing political voice of Small Island Developing States or SIDS on the international stage. This has coincided and grown out of increased attention being paid to climate change and the environment; Small Island Developing States and the Alliance of Small Island States were able to unite behind a common theme and present a common story to the world. This theme was that their very existence as states was being threatened by the consequences of climate change and rising sea levels. This has been perhaps best represented by the passionate portrayal by agents such as the former President of The Maldives, Mohammed Nasheed, and the former Foreign Minister of the Marshall Islands, Tony deBrum (who recently passed away).

Unfortunately, in so doing, these efforts have also fed into this image of islanders as incapable of solving their own problems without outside help. According to this stereotype, if only islands had a little more aid, or a little more expert advice, all of their social and economic problems would be solved. We have encountered this before. Aid and investment that prioritizes technological solutions without addressing some of the underlying social challenges facing islands (including income inequality and opportunity inequality; governance issues) is not likely to lead to long-term, enduring solutions. This narrative is dangerous for several reasons: First, it may contribute to decreasing the self-esteem of the next generation of islanders. This point was made by the noted Pacific anthropologist Epeli Hau’ofa. Also, it may not adequately reflect the apparent nimbleness of islanders; their economic and political entrepreneurship.

Incidentally, more recently, we are seeing governments of some atoll islands, such as the Maldives, playing down the dire forecasts of the demise of their own islands as a result of sea level rise and extreme climate events; realizing that it might have an adverse effect on their ability to attract long-term foreign investment on things like public infrastructure. After all, why would you invest in a new resort or upgrade roads or the airport if they might be washed away in the next twenty years.

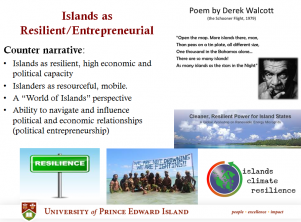

A Counter Narrative

In the past fifteen years, a counter narrative has emerged. This is one in which island economies are seen as resilient. Rather than being isolated and vulnerable, they are adaptable, open, strategic, flexible and nimble to changing circumstances, especially those circumstances such as economic globalization, cultural homogeneity or climate change, that are imposed upon them from the outside. Rather than being remote or isolated, islands are highly integrated into regional and international economies, with ideas and resources being brought back by a mobile population. In fact, rather than being characterized as isolated “islands of the world,” this connected world view is instead characterized by the term “a world of islands.” Islanders are characterized as being resourceful, mobile, and adept at negotiating. Political entrepreneurship is as important as business entrepreneurship. This perspective is as much about the character of the people; the shared identity, their perseverance, and their ability to bring the best ideas back and adapt them to an island context. There is a good quote from my friend and colleague Dr. Godfrey Baldacchino, at the University of Malta, who said that: “For small island states and territories, life continues to be a scramble to exploit one niche or opportunity, then another, moving as nimbly as possible from one to the next or from one crisis to the next as one dries up and (hopefully) another presents itself.”

Of course it would be an overgeneralization to say that all islands are vulnerable or that all islands are resilient. And it is not uncommon for islands to exhibit characteristics of vulnerability while being incredibly successful. Just as there are many endemic species on islands, island economies and societies are also very diverse and unique. But there are some shared characteristics that might be considered more important.

Of course it would be an overgeneralization to say that all islands are vulnerable or that all islands are resilient. And it is not uncommon for islands to exhibit characteristics of vulnerability while being incredibly successful. Just as there are many endemic species on islands, island economies and societies are also very diverse and unique. But there are some shared characteristics that might be considered more important.

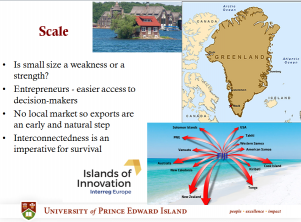

Scale

The first of these is scale. Small size has usually been portrayed as a disadvantage or a weakness of islands because it does not allow for economies of scale and success in a local market before developing an export market. What small scale does mean is a greater likelihood of swings or variations in economic fortune over time. Small size means that many islands do not require a significant upturn in economic activity to make a difference in the livelihoods of islanders. Also, islanders have adapted to this characteristic and have incorporated a variety of mechanisms to counter downturns in economy, including occupational plurality (or generating livelihoods from a variety of activities at the same time).

Scale can also be an advantage. Entrepreneurs have greater access to decision-makers, with fewer layers of bureaucracy in between. In addition to making a living from a variety of activities, islanders also are more likely to play multiple roles. A business person may also be a local politician, who may also be the hockey or soccer coach; who may also be affiliated with an environmental NGO. Not only does this build up a level of trust and familiarity that helps in decision making, but it encourages a broader understanding of the complexity of issues. Increasingly, you are encountering examples of successful niche manufacturing businesses on islands, like the biosciences sector on Prince Edward Island, that have largely ignored the incubator of the local market and are focused, from the beginning, on their knowledge of the export market.

Scale can also be an advantage. Entrepreneurs have greater access to decision-makers, with fewer layers of bureaucracy in between. In addition to making a living from a variety of activities, islanders also are more likely to play multiple roles. A business person may also be a local politician, who may also be the hockey or soccer coach; who may also be affiliated with an environmental NGO. Not only does this build up a level of trust and familiarity that helps in decision making, but it encourages a broader understanding of the complexity of issues. Increasingly, you are encountering examples of successful niche manufacturing businesses on islands, like the biosciences sector on Prince Edward Island, that have largely ignored the incubator of the local market and are focused, from the beginning, on their knowledge of the export market.

Islandness

Every discipline has a jargon that defines it for those within the field as well for the general public. “Islandness” may be one of those words that sets island studies apart from geography, sociology, environmental studies or urban studies, and sets islanders apart from mainlanders. Increasingly, islandness is coming to be associated with the state of mind of islanders as individuals and as part of a larger community. Platt referred to it as “a construct of the mind, a singular way of looking at the world,” that might come from living life around edges and boundaries and closer to nature.

George Putz, a native of Maine, said that islanders are independent, loyal, honourable, frugal and handy. They are tolerant of eccentricity, value both competition and cooperation and have a canny intelligence. Finally, David Weale said that it “becomes part of your being – a part as deep as marrow, and as natural and unselfconscious as breathing.” On small islands there is a deep connection between the economic and the social, and islandness is a part of most businesses. The key here is: to what extent does this “island way of knowing” have an influence on economic and political decision-making and in what ways is this positive and negative.

George Putz, a native of Maine, said that islanders are independent, loyal, honourable, frugal and handy. They are tolerant of eccentricity, value both competition and cooperation and have a canny intelligence. Finally, David Weale said that it “becomes part of your being – a part as deep as marrow, and as natural and unselfconscious as breathing.” On small islands there is a deep connection between the economic and the social, and islandness is a part of most businesses. The key here is: to what extent does this “island way of knowing” have an influence on economic and political decision-making and in what ways is this positive and negative.

I want to spend the rest of my time outlining five recommendations that might improve the future economic well-being of islands.

Recommendation 1: Building Intellectual Capital

Education remains one of the most powerful tools for economic development; not just education in science, engineering and business but also education in the broader interdisciplinary fields that take a global perspective. Even more specifically, I believe there is a need for growth in the number of graduates who understand and are able to carry out research on the unique context of islands. Given my role as Coordinator of an Island Studies Master’s program, I know that I am biased here. But there are very few Island Studies programs when compared to other “area studies” fields. As far as I know, despite the fact that 600 million people live on islands, there are no Bachelor’s programs or PhD programs specific to Island Studies anywhere in the world. And no more than a half dozen Island Studies programs at the Master’s level. All island studies researchers have been trained as geographers, biologists, anthropologists, sociologists, historians, environmentalists and affiliated with these Departments at universities and colleges. I don’t want to be critical of these many scholars, many of whom are at this conference. However, in the same way that northern studies specialists are trained to address challenges that are specific to northern geographies and peoples, island studies PhD’s would be trained as researchers to understand the importance of this context.

There are signs that, at least in the short term, we are entering a period where the world is becoming more insular, as reflected in increasing threats of trade protectionism; the rise of national populism; and an attitude where diversity is seen as a threat rather than as an opportunity. Island scholars bring to the table, through theory and empirical studies, an understanding of the problems brought on by insularity.

There are signs that, at least in the short term, we are entering a period where the world is becoming more insular, as reflected in increasing threats of trade protectionism; the rise of national populism; and an attitude where diversity is seen as a threat rather than as an opportunity. Island scholars bring to the table, through theory and empirical studies, an understanding of the problems brought on by insularity.

Recommendation 2: Measuring Success

We now recognize that measures such as Gross Domestic Product and even the Human Development Index may not adequately measure the quality of life of places. In fact, many island populations are relatively well off when assessed using these measures. For example, Subnational Island Jurisdictions like the British Virgin Islands and Cayman Islands currently have among the highest levels of GDP/capita of any jurisdiction in the world; largely through a combination of financial services and tourism. We probably all know of the following example but it is still instructive to repeat it. In the 1980s, at the height of phosphate mining on the island of Nauru in the Pacific, islanders there were reported to have the highest GDP/capita in the world. A trust fund was set up that was supposed to transition the economy into a post-phosphate era and support future generations of Islanders. Unfortunately, poor investments and allegations of corruption have led to the trust fund being depleted to almost nothing.

Some researchers have been proposing various versions of Vulnerability and Resilience Indices to measure success or potential problems. Inevitably, small islands come out looking very vulnerable when using these indices; both in terms of their economy and their physical environment. Unfortunately, one of the central premises of many of these indices is that the more open and integrated an economy, the more vulnerable it is to decisions and events that are out of the control of that jurisdiction. So we have this apparent contradiction. If an island is self-sufficient and insular, it has a low level of vulnerability. If it is fully engaged in the world economy, it places itself at greater risk. So more attention needs to be paid to how we assess and monitor economic success, both on small island developing states and subnational island jurisdictions.

Some researchers have been proposing various versions of Vulnerability and Resilience Indices to measure success or potential problems. Inevitably, small islands come out looking very vulnerable when using these indices; both in terms of their economy and their physical environment. Unfortunately, one of the central premises of many of these indices is that the more open and integrated an economy, the more vulnerable it is to decisions and events that are out of the control of that jurisdiction. So we have this apparent contradiction. If an island is self-sufficient and insular, it has a low level of vulnerability. If it is fully engaged in the world economy, it places itself at greater risk. So more attention needs to be paid to how we assess and monitor economic success, both on small island developing states and subnational island jurisdictions.

Recommendation 3: Building on the Strengths of Islands and Islanders

As I mentioned earlier, it may be that islandness is the characteristic that most distinguishes Island Studies from every other field of enquiry. From a development perspective, the question is, what role does it play and how do we incorporate it into economic development theories, strategies and policies? Part of the answer is to measure those characteristics that are surrogate indicators of islandness, including a strong sense of place and belonging, the importance of social relationships, occupational plurality, and authenticity.

If, indeed, islandness can be used to advantage, islands have to be cautious that they do not try to mimic the strategies from larger mainland clusters; they will lose that which gives them a competitive advantage; that which sets them apart from the crowd. Instead, they need to invest in the people who have a connection to the island. This includes “Islanders” who have moved away to obtain an education and have succeeded elsewhere, gained experience, established global networks, then are able to bring that back to the island. We have seen that one of the most significant motivations for these return migrants is a desire to be closer to family; to raise their children in an island environment. This in itself is another characteristic of islandness.

If, indeed, islandness can be used to advantage, islands have to be cautious that they do not try to mimic the strategies from larger mainland clusters; they will lose that which gives them a competitive advantage; that which sets them apart from the crowd. Instead, they need to invest in the people who have a connection to the island. This includes “Islanders” who have moved away to obtain an education and have succeeded elsewhere, gained experience, established global networks, then are able to bring that back to the island. We have seen that one of the most significant motivations for these return migrants is a desire to be closer to family; to raise their children in an island environment. This in itself is another characteristic of islandness.

Recommendation 4: Better Understanding of the Roles Played by all Islands

We need to recognize that our world of islands is more than just the Small Island Developing States. There are many more islanders who live on the hundreds of subnational island jurisdictions, including those who live and visit Pingtan Island, than live on island nation states. If we measure success according to some of the traditional indicators like the level of foreign investment and GDP per capita, then some of the most successful islands are these SNIJs. So what is it that allows them to be successful compared to their independent island neighbours?

Is it, in fact, the ambiguous political relationship they have with their metropoles, where they can combine the most beneficial economic features of being islanders while gaining influence and advantage on two fronts; with their metropoles and with the rest of the world through para-diplomacy. The presence, problems and potential of this group of islands and islanders have been largely absent from discussion on the world stage. In fact, it is often even difficult to get statistics on these places because they have been subsumed within the larger state. They need to be brought out from the shadows and be a part of the international island discussion.

Is it, in fact, the ambiguous political relationship they have with their metropoles, where they can combine the most beneficial economic features of being islanders while gaining influence and advantage on two fronts; with their metropoles and with the rest of the world through para-diplomacy. The presence, problems and potential of this group of islands and islanders have been largely absent from discussion on the world stage. In fact, it is often even difficult to get statistics on these places because they have been subsumed within the larger state. They need to be brought out from the shadows and be a part of the international island discussion.

Recommendation 5: Islands as Living Laboratories

Finally, islands have long been described as living labs or closed systems where nature and society could be studied without being influenced by external phenomena. Think for example of the work by Charles Darwin and the evolution of finches on the Galapagos Islands, or studies of the birth and evolution of life on new volcanic islands like Surtsey on the southern edge of Iceland, or the early ethnographers and cultural anthropologists like Margaret Mead writing about social life on tropical islands.

Although the use of the “living lab” metaphor has been criticized, it can be used to advantage as a research tool. For example, the most recent way in which islands have been considered living labs is with respect to their ability to adapt to climate change, including incorporating renewable forms of energy and striving for carbon neutrality. Islands like Samso in Denmark, Gotland in Sweden, and El Hierro in the Spanish Canary Islands are examples of this type of island.

Although the use of the “living lab” metaphor has been criticized, it can be used to advantage as a research tool. For example, the most recent way in which islands have been considered living labs is with respect to their ability to adapt to climate change, including incorporating renewable forms of energy and striving for carbon neutrality. Islands like Samso in Denmark, Gotland in Sweden, and El Hierro in the Spanish Canary Islands are examples of this type of island.

Let me conclude with an admission: I only became an islander, in body and in spirit, late in my life. And I am undoubtedly less qualified to speak of island life than many of you in the audience and the millions of other islanders around the world. However, in a short period of time, I hope I have grown to understand a little bit about islands and islanders. If I have learned one thing, far from being peripheral and disconnected, islands and islanders are central to answering our questions regarding economic change and development.